| INDEX TO ARTICLES |

| CONTACT US |

![]()

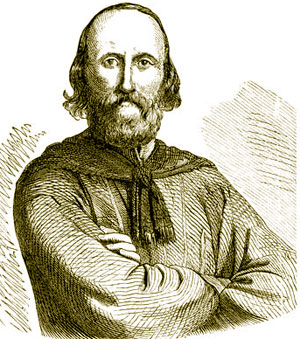

| Garibaldi: A Biographical Profile |

|

By Clara M. Lovett Giuseppe Garibaldi was born in Nice on July 4, 1807, the son of Domenico and Rosa Raimondi. Both parents came from a long line of merchant seamen and small businessmen who moved freely across the political boundary between France and the Kingdom of Sardinia. Giuseppe was still in his teens when he began to a accompany

his father on long sea voyages to Mediterranean and Black Sea ports, the traditional destinations of Ligurian traders. Political ferment and dissent were as much a part of the Ligurian tradition as were sea voyages. When in his early twenties, Garibaldi was drawn into the circle of republican and democratic conspiracies at the center of which was another Ligurian, Giuseppe Mazzini. The conspirators wanted to overthrow the conservative regime of King Charles Felix of Savoy, whose subjects they were. But beyond that, they dreamed of a united Italy free of foreign rule and governed by elected leaders. Insurrection in the Duchy of Savoy was tried, but the attempt failed. Garibaldi had only a marginal role in the insurrection, but his ties with the Mazzinian movement became clear enough to earn him a stiff prison sentence issued in absentia. He was unable to return to his family in Nice and from 1833 to 1835 joined the crews of various ships traveling to the Black Sea, Tunis, and Marseilles. In the latter part of 1835 he accepted a position as second in command on a French merchant ship bound for Brazil. He was captivated by the beauty of that land and by the volatile and exciting political climate, so different from the oppressive conservatism of his native state. Soon he was recruited by rebel forces of the Rio Grande do SuI, who were trying to win their independence from Brazil. From 1836 to 1842 Garibaldi took part in many episodes of the struggle leading to the creation of the Republic of Uruguay. During that struggle he met a young creole, Anita Ribeiro da Silva, who left her husband and children to follow him into battle. He married her in Montevideo in 1842, shortly after her husband's death. Toward the end of 1846 news of political changes in his native Italy reached Garibaldi in Montevideo. There seemed to be a possibility of constitutional reform, if not of revolution, in several Italian states. Eager for a role in those changes, Garibaldi returned to Italy after a sojourn of a few weeks in Gibraltar. Constitutional reform in the Kingdom of Sardinia was followed quickly by the outbreak of war with Austria for control of northern Italy. Like other democratic revolutionaries, Garibaldi saw this war as a prelude to political unification of at least the northern part of Italy and to the transformation of Italian society. He fought against the Austrians (March-July 1848) before joining Mazzini in the revolutionary Roman Republic (February-June 1849). The Neapolitan Carlo Pisacane and Garibaldi bore the responsibility for the defense of the Republic. Their ability and courage, however, were no match for the troops which the French government sent to restore Pope Pius IX to his throne. During the flight from occupied Rome, Garibaldi lost his beloved Anita. He decided, therefore, not to try to join his children, whom he had left with relatives in Nice, but to resume the seafaring life of his youth. The Sardinian consul in Tangier helped him get a job on a merchant ship bound for New York. He remained in that city for about two years (1850-52), earning his bread in a candle factory and joining other European leaders of the revolutions of 1848 in debates and conspiracies. Always a man of action rather than words, however, Garibaldi grew tired of the polemics and dreams that filled the days of many fellow exiles. Once again the sea beckoned, and for nearly four years (1852-56) he traveled to South American and Australian ports. Only in 1856 did it become possible for him to return to Nice safely. Under the leadership of Count Camillo Benso di Cavour, the Kingdom of Sardinia was becoming Austria's chief antagonist and therefore the ally of all those Italians who regarded freedom from foreign influence as the prerequisite for national unity. Garibaldi understood Cavour's policy and supported it openly from 1857 to the unification, even though this meant a sharp break with his Mazzinian friends. As commander of volunteer troops in Lombardy in 1859 and leader of the famed Expedition of the Thousand in 1860, Garibaldi contributed greatly to the making of an Italian Kingdom. His military exploits were as successful as they were daring. But he contributed far more than just his military skills and personal charisma. His decision to fight for "Italy and King Victor Emanuel" was instrumental in securing support for the national revolution from the lower classes in Italian society. In turn, he hoped that reforms by the new leaders would improve the social and economic conditions of the urban poor and of the peasantry. Garibaldi's uneasy political alliance with Cavour and the Sardinian monarchy did not last beyond the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy (March 18, 1861) .There was, of course, the bitter dispute over Garibaldi's birthplace, Nice, ceded by Cavour to France III return for military support against Austria. But beyond that issue, there was Garibaldi's disappointment with the moderate leadership of the 1860s. He resented the reluctance of Cavour's successors to move against the restored papal regime in Rome and to liberate Venetia, which remained under Austrian rule after the war of 1859. And he shared the disillusionment of the Southern peasants with a government that taxed their daily bread and drafted their sons into the army yet seemed indifferent to their basic needs. From 1862 to 1867 Garibaldi remained a focal point of democratic opposition to the liberal governments and of attempts to overthrow the papal government in defiance of international treaties. He was also a key figure in an international network of revolutionaries who fought for independence from Austria and Turkey in Hungary and in the Balkans. Although he was elected to Parliament in the 1860s, Garibaldi was uncomfortable with the life of a deputy and with the slow unfolding of the legislative process. He was much more at ease (and probably more effective) as leader of public rallies in favor of domestic or foreign causes in which he believed. Among these were universal suffrage and legal equality for women, the right of workers to organize, freedom of press and worship, and Poland's freedom from Russia. In his declining years Garibaldi continued to play a role as unofficial leader of the democratic opposition and to make public appearances. But between public appearances he preferred to stay at the plain farmhouse he had purchased on the rocky island of Caprera off the Sardinian coast. His habitual frugality and the simplicity of the surroundings invited a comparison with Rome's Cincinnatus. The most popular of the men who "made Italy," he died at Caprera on June 2, 1882. By his expressed wish, Garibaldi was not given a state funeral. His ashes were scattered over the blue waters of the Mediterranean, which had been so much a part of his life. Clara M. Lovett was the former Chief of the European Division of the U.S. Library of Congress. |