| HOME |

| INDEX ARTICLES |

| CONTACT US |

|

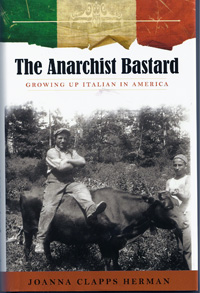

The Anarchist Bastard ~ Growing Up Italian in America

![]()

June 19, 2011 ~ As alluring and romantic a notion as it might be, “la dolce vita” never truly applied to all Italians, and certainly not to those who left Italy to improve their lives in America. Similarly, growing up Italian American was far more nuanced than the typical picture of huge family gatherings, a table spilling over with sumptuous foods, and Nonno at the head of the table presiding magnanimously over his happy, laughing brood. Yet, much of the literature written by and about Italian Americans has mostly perpetuated this sentimental view.

One of the difficulties an Italian American writer faces is revealing raw truths about one’s family. Difficult, because of the unwritten rule that Italian family members do not air their dirty laundry in public. Doing so is a sign of disrespect and disloyalty to the family. A family's skeletons stay in the closet, and often remain hidden, even father from son, mother from daughter, husband from wife, but certainly and always from strangers.

One of the difficulties an Italian American writer faces is revealing raw truths about one’s family. Difficult, because of the unwritten rule that Italian family members do not air their dirty laundry in public. Doing so is a sign of disrespect and disloyalty to the family. A family's skeletons stay in the closet, and often remain hidden, even father from son, mother from daughter, husband from wife, but certainly and always from strangers.

But in the new book Anarchist Bastard by Joanna Clapps Herman (yes, Clapps is an Italian surname and can be found in some phone books of the Basilicata region), the author treads where few others have dared. In what must have been a personally difficult decision, Clapps tells the story of her Italian American family’s life in Waterbury, Connecticut. Her tale covers the good and the expected, and relates experiences that many Italian Americans will easily identify with. What sets the book apart from other Italian-theme literature, however, is that Clapps also bares many of her family’s failings and serious flaws, shedding light on some dark corners of the family’s past.

In so doing, Clapps reveals themes that have largely been omitted by other Italian American writers--the bitter and critical grandmother, the alcoholic grandfather who badgered and beat his wife to submission. It must have been hard for Clapps to cover this territory but it had to be done for the sake of integrity. In fact, what family can claim that no such relative ever existed in their family tree? Clapps deserves merit for depicting her family in such a realistic manner, validating the experience of other Italian Americans who may have grown up in similar households.

However, while the mission of telling her story, warts and all, is commendable, the execution could have been better. For one, the title distorts the contents. The book is not entirely about her grandfather's anarchist views, in fact, his politics are mentioned in only one chapter. The book is really about the stark reality that in some Italian-American families all was not sunny, that, unfortunately, women were sometimes ill treated and subservient to abusive, alcoholic, emotionally absent husbands, and that wives could be bitter and cold.

Aside from the off-putting title, the book is disjointed and difficult to follow. Clapps could generally have used a good editor, one who would have resisted her decision to take the easy way out and quote family members verbatim for chapters on end, rather developing their characters and having the story progress in a more dynamic way.

The author might have begun her tale with the fascinating anecdote that she reveals toward the end of the book: that her grandfather owned the foundry in which sculptor Alexander Calder's works were forged. This would have been a far more interesting starting point from which to introduce and develop her family history. Further, the book should have included a chart of her family tree to help guide the reader through the confusing thicket of relatives.

Aside from these considerable weaknesses, the book is ground-breaking and commendable. It is a book that goes beyond rosy stereotypes and gets closer to depicting reality. It is a book that all generations of Italian Americans might read and use as a basis for further discussion on what it really means to grow up Italian American. ----CiaoAmerica! June 19, 2011

Excerpts from the book

"The rules were these: If you are the guest, don’t be 'Merican. Never take any food that you are offered. Not at first, even if you are at your aunt’s house. You must refuse any and all food when it is first offered. "Oh, no thank you," you say, "it looks delicious, but I really couldn’t. We just finished eating."

Only after the food has been offered over and over, then put on a plate in front of you and the host has insisted repeatedly, "Try some. I just made it this morning," are you even to consider eating a modest portion and saying, "Well, if you insist." Then, "Mmmmm, delicious. That’s so good. Thank you so much. I couldn’t possibly eat another morsel, spoonful, bite, sip." In fact the food always is delicious, scrumptious, delectably sweet, perfectly salted –we like a lot of salt—crisp, fresh. Whatever it should be, it is.

If you are the host you never ask, "Would you like a piece of 'a bizz’?" That would put your guest in the terrible position of overtly having to announce that, yes, they would like something. It would be a profound embarrassment for both guest and host. Showing desire of any kind reveals that you are wanting. As the host your job is to put as much food on the table as you can, to burden the table with food and drink, far beyond the limit of what actually makes sense for you to offer. As a guest you are to limit yourself to a highly appreciated, small amount.

These rules and customs are based on a culture of scarcity of the very old world in southern Italy and Sicily, where it would have been terribly shameful to show any hint of actual scarcity in your household. These rules helped everything keep a balance. The host would offer and save face and the guest would partake of their offerings and reveal nothing."

Last updated July 20, 2011 | CiaoAmerica.net|